Nostalgia Mathematica

Last updated: January 6, 2024

“Traveling together like this makes me feel like we’ve returned to those days”

- Sousou no Frieren

They say nostalgia is a thing for old people.

Why worry about the past when you are young?

But to consider the past insignificant is akin to throwing away one’s identity.

At 18, there have been some amazing moments in my life that I look back on sentimentally.

But it always feels like these life-defining moments were never experienced “in the moment” so to speak.

The feeling of wanting to return to some time, to have a second chance to experience something fully is very well the definition of nostalgia.

And to sprinkle some math into philosophical thought, I’d like to present to you why.

The most important idea to start off with is that we are always moving. Sit yourself down. You suspend yourself in space, but not time. As long as time travel is impossible, and disregarding time zones, it’s impossible to stop the movement of time. Let us denote time as \(T\).

At any moment in time, we exhibit a state of being. In simple terms, somewhere on the scale between happiness or sadness. In a more nuanced way, it can be described as our contentness regarding our current circumstances, which may be different for every person. Consequently, let us denote our state of being as \(S\).

Therefore, it makes sense to define a life function \(L\) with \(L(T) = S\). In non-mathematical terminology, every moment from when you were born to you reading these words can be mapped to some emotional state of being.

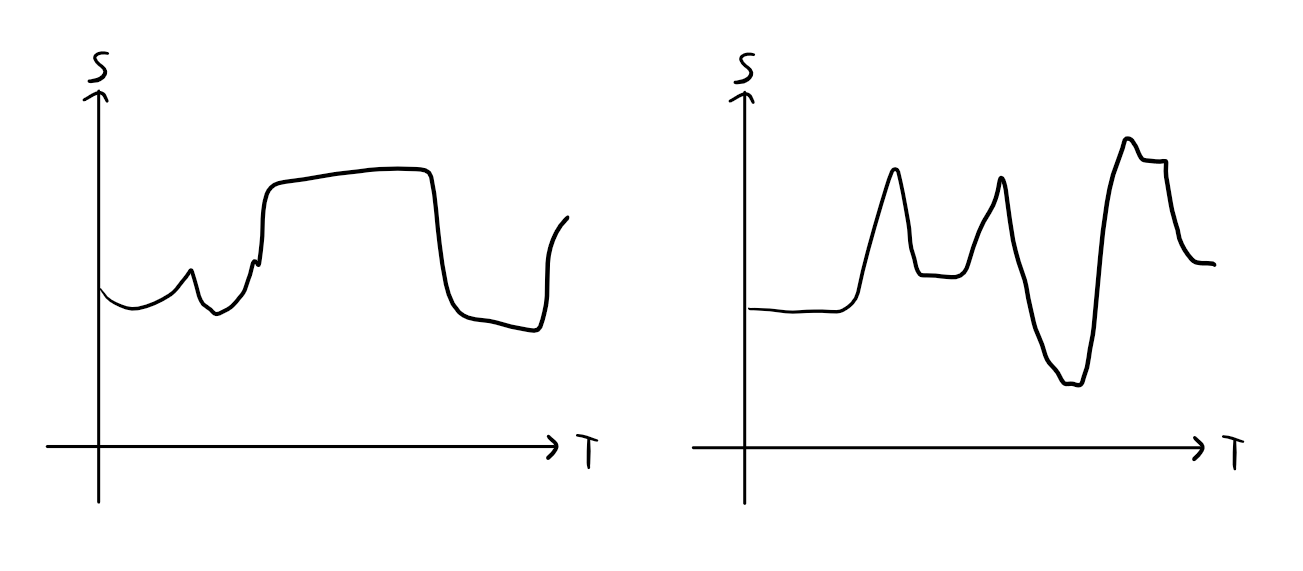

Consider the period of time from your earliest memories until now. Unless you’ve been in a coma for years, \(L\) is a continuous function, meaning that when plotted as a graph with \(T\) as the independent variable and \(S\) as the dependent variable, we would get a curve with no breaks in it, such as the following:

Looking at these graphs, (and by the extreme value theorem, if you are a math nerd like me), there is a point in time \(t\) where \(L(t)\) reaches a maximum value. Call this value \(s\). It represents the most significant moment of your life so far, such a moment that might come up first when experiencing a feeling of nostalgia. The “best moment of your life”.

However, memories are just memories. Consider a memory at a particular moment in time. This might be something you look back really fondly right now, for example an outing with friends, a first date, a great accomplishment.

But as time moves forward, things change. Relations with friends may sour, a breakup, a career change. Cherished moments fall by the wayside, sometimes becoming painful or embarassing to think about. While these moments may still be meaningful, they no longer represent the best moments of our lives. Similarly, the opposite can also happen. Events labelled as irrelevant or depressing when they happened may turn out to be of great significance in hindsight.

What does this tell us? That as time progresses, our life function \(L\) also changes. How we perceive an event in the past depends on our beliefs and values in the present.

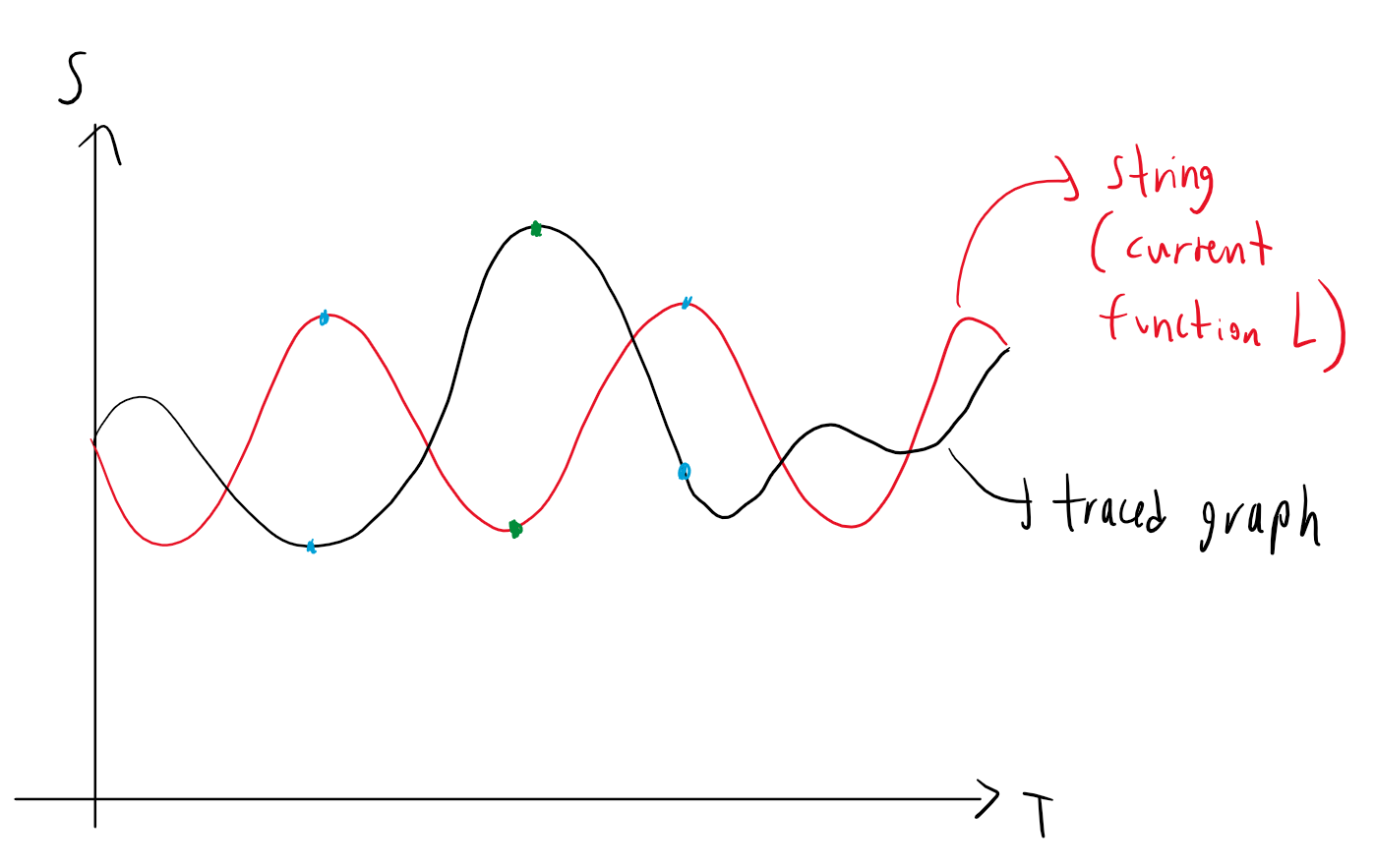

In graphical terms, imagine a pencil tracing a string oscillating up and down, moving forward on the time axis. The position where the pencil tip is at right now is the present. Trailing behind the tip is the past, mere memories. Since the string is oscillating, as we move forward in time, the string changes position relative to the graph that was traced. The oscillation of the string represents our deviation between our current memory of an event and how it was perceived in the past:

Therefore, the string can be considered as the function \(L\), always changing as the string oscillates. The traced graph represents how we perceived the event exactly when it happened.

So what is the significance of this? By observing the graph, we can see points in time highlighted in blue, for which when we experienced the event (represented by the curve in black), were nothing special. However, based on our current life function \(L\) as the red curve, these moments might as well be the best moments in our lives, high on the \(S\) axis. On the other hand, the point highlighted in green represents quite the opposite, an event that we considered with great signficance when it happened, but something that hardly crosses our mind based on our current life situation.

And so this is my convoluted “proof” for why nostalgia is observed. To summarize, events we don’t consider as significant in the moment change as our beliefs and values change. Experiencing new things, and even the nature of time contribute to this as well. We didn’t bother enjoying these moments because they might have been irrelevant in the moment. But now we want to go back because we understand what it was about such an event that was so important to us.

The word “nostalgia” comes from the Greek nostos, meaning ‘return home’ and algos, meaning pain. Pain from not being able to return and experience a now-significant event ever again. Pain from not realising that an event was significant when it happened. Hindsight is always 20/20.

And maybe in another decade the same event might just fade into irrelevancy once again.

Obviously a mathematical explanation of a human condition that is defined by irrationality is in no way rigorous, and so I would like to talk about my own experience.

Just less than a year ago, in March of 2023, I took a two-week trip to China to visit family. However, due to reasons beyond my control, this trip meant that I would have to miss an entire week of school. Being in IB, this meant a lot of catching up to do (I actually had to do a chemistry presentation the day after I got back). I was dealing with many things during this time, academic and personal, and so during this trip to China I spent a lot of time making sure I wasn’t getting behind on schoolwork, while also feeling generally left out due to the lack of internet leading to an inability to access my friends back home.

While this was happening, I was feeling somewhat miserable, even if it meant meeting many relatives who I’ve never seen in a long time and going places I’d never been. But it was only when I got back to school and the mundane rhythm and responsibility returned that I realised that my trip to China was one of the more enjoyable and insightful moments of recent memory.

And when I look back on it now I realised the impact that it had on my life. I celebrated my 18th birthday with all my relatives, had the freedom to wander around the city, and stuffed myself at restaurants every day. And to realise that worrying about the past or the future is what prevented me from enjoying the present to the fullest is one of the most insightful lessons I learned from this trip. In relation to what I previously stated in this post, this also goes to show how a memory of an experience changes over time depending on one’s worldview.

With the winter break coming to a close, and a hard 1B term awaiting me (pls gimme job I beg), I believe that I will look back on the memories of the break in a similar manner. However, it is important to note that just because there were better times in the past doesn’t mean there won’t be better times in the future. To believe so is to accept the fact that you’ve already peaked in life and it’s all downhill from here. Your next great adventure is waiting to happen.

Anytime.

Anywhere.